'Frank' Hudleston by Arthur Machen

'Frank' Hudleston by Arthur Machen

|

|

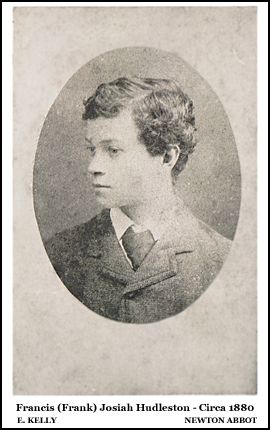

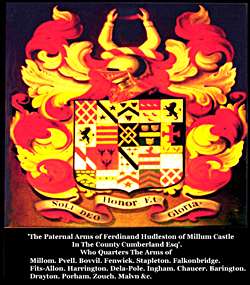

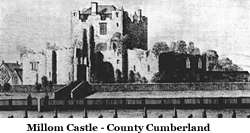

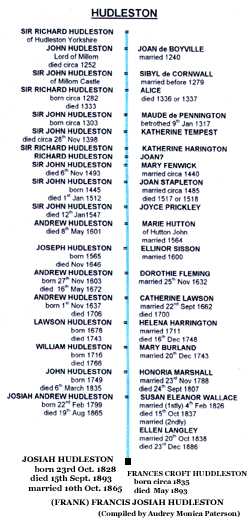

The following is reproduced from a biographical foreword in Frank's book - "Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne" - published by Johnathan Cape in 1928. I have added a few illustrations. My maternal grandfather 'Frank' died from diabetes in 1927 and I deeply regret that I never met him. - David Hyde 'Frank' Hudleston - A Biographical Note- by Arthur Machen FRANCIS JOSIAH HUDLESTON, late Principal Librarian of the War Office, and author of Gentleman Johnny Burgoyne, was descended from one of the oldest families in England. In the year 1109, as Mr. Ferdinand Hudleston, of Hutton John, informs me, one Nigel, being an old man, gave certain lands in Huddleston, in Yorkshire, to Selby Abbey, and became a lay brother there for his soul's health. Nigel of Huddleston held his lands from the Archbishop of York, to whom the Conqueror had granted ten or twelve Knights' fees. All who held land of the king were bound, in return, to perform military service. Such service was forbidden to an ecclesiastic; consequently the Archbishop portioned out these fees to warriors, and of these warriors, Nigel. of Huddleston, holding the two first fees, was chief. The fees descended from father to son for two or three generations. About 1240 John de Hudleston married Joan Boyvill of Millom Castle, heiress of the Boyvills, and from that date to 1745, when Elizabeth Hudleston, heiress, married Sir Hedworth Williamson, Millom remained the chief seat of the family.

They were a mighty race of fighting men. The second of the name to hold Millom fought at the Battle of Falkirk (1298), and appears on the famous Roll of Caerlaverock. Another of them, adhering to Lancaster, obtained a pardon for his share in the murder of Piers Caveston. In 1335 John de Hodelston was given a licence to crenellate - that is, fortify - his dwelling at Millom. In 1415 Sir Richard fought at Agincourt. Later, another of the race married a natural daughter of Nevill the Kingmaker, and so allied himself to Richard Ill. This, according to Mr. H. S. Cowper, author of Millom Castle and the Hudlestons, was the golden age of the family. The Hudlestons were in high spirits. A manuscript of the early seventeenth century speaks of them as making Millom Castle 'still their dwelling place and abode, holding themselves content, that the old manner of strong building there, with the goodly demesns and commodities which both land and sea afford them, and the stately parks full of huge oaks and timber woods and fallow deer do better witness their ancient and present greatness and worth, than the painted vanities of our time do grace our new upstarts.' A fine spirit, well befitting a fine old family; but a little earlier one of the family allowed cheerfulness to break through beyond due measure. He flourished in the age of Queen Elizabeth, was a 'great Swash buckler' and 'great gamester,' and 'lived at a Rate beyond his incomes.' He was asked by a Countess how he lived so gallantly, and he replied. 'Of my meat and drink' - a remark worthy of Touchstone in his deadliest vein.

The seventeenth century was not fortunate for the Hudlestons. The Great Rebellion came. Ferdinand Hudleston had nine sons, every one of whom fought for the king. Sir William, fourteenth lord of Millom, raised a regiment for Charles. John Hudleston was a colonel of Dragoons. The wrong side won, and Millom was sequestrated and its owners heavily fined. The Restoration brought no return for such loyalties. In the last quarter of the century, two Hudlestons died in debtors' prisons. The family had been steadfast sons of the Roman Catholic Church, and as steadfast followers of their sovereign. But considering this matter of high service rewarded by the debtors' prison, it is not surprising that in 1689 the Hudlestons had become Anglicans and eager partisans of William of Orange.

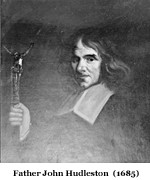

From the main stock of Millom many branches of the family proceeded. There were the Huddlestons of Sawston, Cambridgeshire, Hudlestons of Gloucestershire, Huddlestons of Lincoln, and Hudlestons of Hutton John, a noble, grey old house, with a peel tower, on the borders of the Lake District, six miles from Ulleswater. To this branch belonged the famous Father John Hudleston, the Benedictine, who helped King Charles II. to escape after Worcester, and received the dying king into the Roman Catholic Church. Of these Hudlestons of Hutton John came Colonel Josiah Hudleston, of the Madras Staff Corps, who married Frances Croft Huddleston - no relation, odd as it seems. Francis Josiah Hudleston, their son, was born at Madras on October 15th 1869. F. J. Hudleston was educated at Newton College, Newton Abbot, where, I think, he was contemporary with Sir Arthur Quiller Couch. He became an assistant at the British Museum about the year 1890. A few years later the Intelligence Department of the War Office required an Assistant Librarian. Application was made to Dr. Richard Garnett, then Keeper of Printed Books. He recommended Hudleston, who took up his duties, first at the Library in Queen Anne's Gate, then at Winchester House, St. James's Square, and finally at the new War Office in Whitehall. In 1902 he became Principal Librarian, and he was working at the Library within a few weeks of his death on November 29th, 1927.

So much for Francis Josiah Hudleston. Now for 'Frank.' To begin with, I may say that he was my friend for thirty-one years, my brother-in-law for twenty-four of these. So I knew him well, and the first thing that occurs to me to say is, that you might know him all your life and never gather from him that he was a devoted, industrious, and brilliant Librarian and a master of Military History. And still less would you gain so much as a hint from any word of his that he was a member of one of the most ancient and chivalrous families of England. As to the work at the War Office, after one had known Frank for some years, a few words would rarely escape which seemed to show that he was acquainted with the place, and loafed about it in an easy, amused sort of fashion on several days of the week. 'I don't know what to do at the W.O.,' he once observed in the family'. 'I found myself reading Macaulay the other day, just to pass the time.' So he would occasionally relate little incidents of the office that had whiled away for a time his (feigned) boredom. It was at Winchester House, I believe, that Frank's window had a view of the room of a distinguished officer of the Intelligence Department. It was at once a perplexity and a joy to Frank to note that this officer, as he sat at his desk, was overcome at frequent intervals by convulsions of mirth: he would lean back in his chair and give way to fits of uncontrollable laughter. 'And when the major went from Winchester House,' Frank would relate, 'it was found that he had left his safe locked. It was supposed to be full of secret documents of the greatest importance, and a sort of High Commission was assembled to open it. And when they did get it open, there was nothing inside but an old pair of trousers and an improper French novel.' Frank seemed to think that, while the contents of the safe did not exactly solve the problem of the major's mirth, it indicated at least the lines on which a solution might be attempted. And so, a few months ago, soon after the publication of his Warriors in Undress, he was discussing the character of the Duke of York with a general. He showed the general a portrait of the duke's friend, Mary Anne Clark. 'She does look a saucy little . . . lady,' said the officer, and forthwith intoned with full voice the famous chant: 'The famous Duke of York,' to the delight of the Librarian and his assistants. Frank was delighted, some years ago, when the Territorial Forces were being organised. Mr. Haldane, as he was in those days, asked to be furnished with the whole literature relating to Cromwell's New Model, and Frank drew a lively picture of the New British Army in Buff jerkins, armed with Pikes and Matchlocks. That was the War Office if you listened to Frank: a home for farceurs and idlers, of whom he was chief. I think he convinced many or most of his friends that such was the state of affairs in Whitehall. One of them was congratulating him on his easy job and idle hours. He wagged an indignant finger, and said: 'The W.O. Library is a Hive, a Busy Hive; and don't you forget it.' But the tone and manner were so burlesque that the man was confirmed in his view.

There was not a word of truth in it. F. J. Hudleston made the War Office Library as it is now. He was one of the most energetic and systematic officials that the Civil Service has ever known. He had acquired, through years of hard work, a knowledge, not only of the outsides and titles of his thousands of volumes, but also of their contents, down to the minutest details. An instance of his extensive and peculiar information was given by one of his chiefs, in a letter to a relative. The matter was thus. A distinguished American, highly commended to the Office, called on the Chief in question, and asked if the authorities could give him any information as to an ancestor of his, General Renselaer van Kruger - we will say - who commanded the Colonial Forces at the Battle of Chickamauga Lick, in the War of Independence. The great man at the W.O. had never heard of the general or the battle, and confessed as much. 'But,' he said, 'I'll take you down to the Library. Our Librarian, Hudleston, may possibly be able to help you.' In five minutes Hudleston had 'wised up' Mr. van Kruger. He provided him to the fullest extent with information about General van Kruger ? an officer of no great consequence and about the stricken field of Chickarnauga Lick - a third rate skirmish, of no consequence whatever; and, further, he told the American inquirer what books to consult as to the matter which interested him. Frank Hudleston knew his subject, not merely broadly, but microscopically: he was, indeed, the Compleat Librarian. And it is rumoured that in the early period of his career at the War Office, his activities were not wholly confined to the books in the Library. One of his sisters found herself at a dinner-party, sitting next to that well-known officer, Sir George Tappleton. He seemed interested in her name. 'Are you by any chance,' he asked, 'related to F. J. Hudleston of the War Office?' 'I'm his sister.' 'Indeed; you don't say so. You must be extremely proud of your brother. That affair of the Blank Cypher was a wonderful piece of work; of the greatest value to the country.' Miss Hudleston had never heard of the Blank Cypher, and wanted, naturally, to know all about it. 'You don't mean to say that your brother never told you? Well, the fact is that he succeeded in solving the Blank Cypher, and the importance of that was so great, that he was personally thanked by Lord Roberts.' Frank's sisters poured congratulations on him. He seemed annoyed, murmured that he believed that something of the sort had happened - and changed the subject. No man had a keener scent in tracking down a secret. And when the secret had been found, his capacity for keeping it was infinite. There were many points in common between him and Mr. Nadgett, 'man of mystery to the Anglo-Bengalee Disinterested Loan and Life Assurance Company.'

Apart from the Office - and, as I have stated, it was very rarely that he spoke of the office outside it, and then only in the manner of burlesque - 1 would say that to him life was presented under the species of whimsicality. He revelled in all oddity, all absurdity, all the more comic anfractuosities of humanity. He took all queerness for his province. He used to delight in telling stories of his early days at the British Museum, where there still lingered, both among the Assistants and the Readers, some of the strangest characters in London. Among the Assistants there was an old gentleman who was given to talking to himself in the oddest manner. He would be heard to murmur confidentially: "E gave out umbrellas,' and when asked of what he had partaken at a dinner which he had attended, he replied easily: 'Oh, soup and that, y'know.' Then there was a reader who suddenly rose in her place and cried to the great dome that Mr. Blank (one of the chief Assistants) was an impertinent jackanapes. Everything odd was treasured to tell to Frank, everything fantastic was a delight to him! He strolled the streets with an eye cocked to perceive humorous entertainment; he peered out of his window on the world, eager for the manifestation of the comic spirit. He used to tell how Lord Morley, in his later days, sitting by the fire at his club, sipping a pint of choicer port, would be observed to be chuckling to himself over singular memories; and so Frank Hudleston, though he loved congenial company, was always ready to sit alone in the snug corner of some quiet tavern, relishing the memories of the queer things he had seen, and the queer people he had known in the course of his observant life. I have noted his love of a secret, and this propensity, no doubt, accounted for his strong interest in detective stories, and crime stories, and mystery stories of all sorts. With this he coupled, oddly enough, a great admiration for the poetical works of Alexander Pope. I am sure he would have heartily echoed Dr. Johnson's question as to Pope: 'If this is not poetry, what is poetry?' He was a great lover of cats, and was heard to boast that he could make any cat come to him. Two works devoted to these noble animals survive in manuscript. 'The Cat Book,' a volume of lyric poetry, and 'Mauser,' a prose tale relating to a select circle of cats with which he had mingled when a resident at Harrow. He often expressed his feelings through the medium of verse. Early in our friendship, 1 came upon him one evening sitting by himself in a retired corner of the vanished Cafe de L'Europe, in Leicester Square, writing diligently. He showed me the poem, which was headed. 'To One for Whom I have no particular Respect.' It accused one of the most important personages of the British Museum of a series of hideous offences, committed from the days of his cradle onwards. 1 found out that Frank had never spoken to this entirely blameless and inoffensive man - but he disliked the way in which he trimmed his beard. I will give one example of his poetical gift. He was living with us at the time, and he had a fancy for cider. He expressed his desire in these classic lines: Harrow Road There runs a road to Harrow Hill, The Harrow Road they say it is, Ten minutes' walk from Lisson Grove, An ancient pilgrims' way it is. And here, oh here, house?agents cry, Are many priceless properties. But far the best is Shattock's (Tom) A famous cider shop it is. Here, where the ancient Britons came, From Homer Row and Bell Street, too, The cider still remains the same. Thus this hard-working, valuable, brilliant man loved desipere in loco. I am keeping a sharp look-out for all the queer things I may chance to see, so that I may have something good for him when we next meet. ARTHUR MACHEN |

|

|

|

|

|